The Septuagint is a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. Scholars date the translation of the Torah – the first five Books of Moses – back to the third century BCE during the time of King Ptolemy II in Alexandria, Egypt. The remaining portions may have been completed as early as the second century BCE. Although the name suggests the number “seventy,” the Talmud states the translation of the Torah was by seventy-two elders, isolated from each other, who each produced identical translations. “Septuagint” is often abbreviated “LXX” (the Roman number 70).

This article isn’t a critical look at the Septuagint. You can find several sites where you can read that information. I want to consider this translation and the Scriptures we commonly use in light of our walk with Yeshua. Are we missing anything, or being influenced by something that has been changed?

A study of the timeline of various canons of Scripture can be complex. The commonly accepted text of the Hebrew Bible today is the Masoretic text, dating back around the seventh century and certainly no further than the fifth century CE. A completed form probably emerged around 1000 CE.

The Hebrew Masoretic Text

The Masoretic text is the “official” text of Rabbinic Judaism and is the primary source for the Old Testament in most Christian Bibles. The King James Version (KJV) and older Christian Bibles use an early edition, while most modern translations use Kittel’s Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS). The Jewish Publication Society (JPS) Tahakh uses the BHS text, and the Stone Edition Tanach appears to use a “corrected” text of the earlier edition (the exact text is not clearly stated).

There are several variations between the Greek Septuagint and the Hebrew Masoretic text. In the preface to most modern Bible versions, you will find some sort of wording indicating that, in addition to the BHS, they consult other sources including the Septuagint.

Then God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.” Thus God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament; and it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven. So the evening and the morning were the second day (Genesis 1:6-8, NKJV).

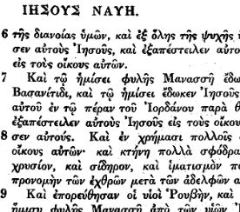

And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the water, and let it be a division between water and water, and it was so. And God made the firmament, and God divided between the water which was under the firmament and the water which was above the firmament. And God called the firmament Heaven, and God saw that it was good, and there was evening and there was morning, the second day (Genesis 1:6-8 LXX).

An Interesting and Revealing Timeline

I do not claim in any way to be an expert on these source texts. I think it is important, however, to consider the timeline. The Masoretic texts, including the first appearance of any vowel pointing, emerged somewhere between 500 CE and 1000 CE – about the same time as the beginning of Islam. Were they in any way influenced by a bias against Yeshua as the promised Messiah? Were these Masoretes accountable to anyone other than themselves as they completed this work?

The Septuagint includes several books that are not a part of the Masoretic texts, and thus are not included in the canon of the Hebrew Tanach or of most protestant Christian Bibles. Why did the Masoretes leave out something that these seventy Hebrew elders included nearly a thousand years earlier? Why do most protestants follow suit?

The Greek Septuagint, dating before the time of Yeshua, was translated from something. The original Hebrew text it was translated from is no longer extant. Not to be promoting some kind of conspiracy, but one has to ask – was that by design? When did those texts cease to exist?

New Testament Quotations

Many Old Testament (Tanach) passages quoted in the New Testament don’t match. It is often explained that the New Testament quotes the Septuagint while the Old Testament is primarily from the Masoretic Text. That could be true, but I think there may be another explanation.

Sacrifice and offering You did not desire; My ears You have opened. Burnt offering and sin offering You did not require (Psalms 40:6 NKJV).

Sacrifice and offering thou wouldest not; but a body hast thou prepared me: whole-burnt-offering and sacrifice for sin thou didst not require (Psalms 40:6 LXX).

Therefore, when He came into the world, He said: “Sacrifice and offering You did not desire, But a body You have prepared for Me” (Hebrews 10:5 NKJV).

There is much debate over the language in which the New Testament documents were originally written. We have a few old Hebrew texts of some books or letters, but they may well be translations. Personally (and again, I am not claiming to be an expert), I think for the most part things that were originally spoken or passed down in Hebrew or Aramaic were later written down in Greek, the common written language of the day.

I doubt many people in Israel in Yeshua’s time would have had or even seen a copy of the Greek Septuagint. So how would they quote it? I don’t believe they did. I think they verbally quoted Scripture passages from the Tanach in Hebrew, and I think someone later wrote down in Greek what they were hearing in Hebrew. I am suggesting that the Greek New Testament does not quote the Septuagint, but that it states something in Greek quoting the same Hebrew text from which the Septuagint was translated – a text that no longer exists and is not the same as what we have been given by the Masoretes.

“The Spirit of the Lord God is upon Me, Because the Lord has anointed Me To preach good tidings to the poor; He has sent Me to heal the brokenhearted, To proclaim liberty to the captives, And the opening of the prison to those who are bound; To proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord…” (Isaiah 61:1-2 NKJV).

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me; he has sent me to preach glad tidings to the poor, to heal the broken in heart, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and recovery of sight to the blind; to declare the acceptable year of the Lord… (Isaiah 61:1-2 LXX).

And He was handed the book of the prophet Isaiah. And when He had opened the book, He found the place where it was written: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon Me, Because He has anointed Me to preach the gospel to the poor; He has sent Me to heal the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed; to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord” (Luke 4:17-19 NKJV).

The New Testament either quotes the Septuagint or quotes a non-extant Hebrew text from which the Septuagint is translated. So the Greek Septuagint, and a reliable English translation of it, should be important to believers in Yeshua. In fact, to discredit the Septuagint is to discredit the New Testament. Might this also be an agenda of those creating the Masoretic text? I am not suggesting that the Septuagint is perfect, but those of us returning to our Hebrew roots sometimes tend to shun anything Greek. This is certainly a valuable reference.

Whatever you believe about the original language of the New Testament or the validity of various texts of the Hebrew Bible, I would recommend that you consider adding a copy of the Septuagint to your reference library. Here are a couple of suggestions.

Selecting these links opens a new window at Amazon.

If you have additional thoughts on the Septuagint, please leave a comment.